How do Aussie grantmakers measure up against the United Nations’ social development goals?

Posted on 11 May 2022

By Matthew Schulz, journalist, Our Community

Australian grantmakers are on a mission to make the world a better place, but how successful are they really?

Our Community’s Innovation Lab has crunched the numbers to see how well grantmakers’ funding aligns with the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

The Future of Funding: How well are Australian grants addressing the UN Sustainable Development Goals? examines $6 billion distributed via the SmartyGrants platform in eight years.

The SDGs span funding for the economy, society and the biosphere across 17 goals.

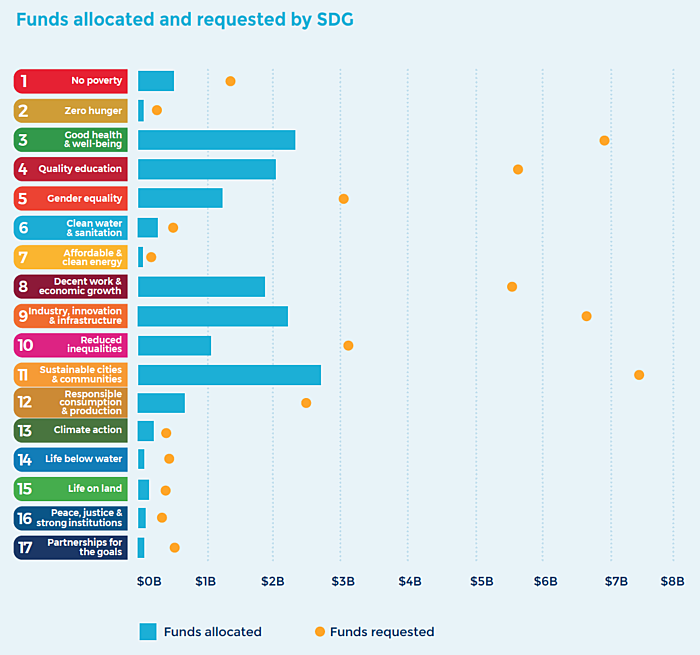

Assessing the activity of more than 440 grantmakers, the 53-page report reveals:

- the top five priorities (by dollars spent) for Australian funders using SmartyGrants were:

- sustainable cities and communities (SDG 11), $2.7 billion

- good health and wellbeing (SDG 3), $2.3 billion

- industry, innovation and infrastructure (SDG 9), $2.2 billion

- quality education (SD 4), $2 billion

- decent work and economic growth (SDG 8), $1.9 billion

- the bottom five priorities for SmartyGrants funders were:

- affordable and clean energy (SDG 7), $55 million

- zero hunger (SDG 2), $83 million

- partnerships for the goals (SDG 17), $100 million

- life below water (SDG 14), $109 million

- peace, justice and strong institutions (SDG 16), $114 million

The report comes as increasing numbers of Australian grantmakers seek to align their funding to the SDGs, or ask their grantees to do so.

Funds boost for climate action

The chart above shows changes in priority given to each SDG across time. The thickness of the line represents the volume of applications.

Those trends remained fairly consistent over the study’s timeframe, with even the world-changing impact of covid-19 doing little to shift SDG spending trends.

There have been significant shifts in some spending in recent years, however, with funding for gender equality (SDG 5) steadily dropping after a high in 2017. Funding for good health and wellbeing (SDG 3) showed a similar dip.

Perhaps the most significant trend highlighted in the report was a fourfold increase in the proportion of grants funding aimed at climate action (SDG 13) in 2020, though coming from a low base. It was up from 0.9% to 3.4% of total grant spending. Approval rates for this SDG also showed a dramatic increase, from one quarter to two thirds.

The study showed a 20% increase (from a low base) in spending on other biosphere goals:

- clean water and sanitation (SDG 6)

- affordable and clean energy (SDG 7)

- life on the land (SDG 15).

Spending on grants that substantially address climate issues (such as SDG goal 11 – sustainable cities and communities) now makes up 17% of all SmartyGrants funding and is the top ranked segment for funding allocation. Demand for those funds vastly exceeds supply.

The report noted that separate studies had found that research funding related to the biosphere goals, while not captured in the SmartyGrants statistics, was on the rise. Climate action (SDG 13) and life on land (SDG 15) are now top five priorities among researchers, but funds are not yet being allocated to direct action.

Funding priorities vary by grantmaker

Different kinds of funders had different priorities:

- philanthropic groups gave greater weighting to health and wellbeing (SDG 3)

- local, state and territory governments gave sustainable cities and communities (SDG 11) top billing

- the federal government continued to prioritise gender equality (SDG 5).

Grantmaker goals critical to measuring outcomes

Report author Paola Oliva-Altamirano said that while more funders than ever were focused on understanding and measuring their impact, it was critical that they first set the goals they would measure against.

“The process of considering the goals and setting road maps to achieve [SDG indicators] in different scenarios is as important as the outcomes. Once you have clear goals, then you can move to the next stage of measuring impact.”

Dr Oliva-Altamirano said that grantmakers should consider the report’s findings about SDGs and funding priorities alongside their outcomes measurement models (or “theories of change”) to understand that impact.

Measurement tools such as the SmartyGrants Outcomes Engine can help fine-tune that understanding, she said.

Dr Oliva-Altamirano said funding distribution in Australia “could be considerably improved” if grantmakers asked these key questions before, during and after rolling out their programs:

- How do we engage with the community?

- What role do the SDGs play in program design

- How were the different populations represented in the program?

Benchmarking is easier if you compare apples with apples

A group of panellists discussed the report and how funders can incorporate the SDGs into their program design in a recent webinar (watch the recording here) hosted by Dr Oliva-Altamirano.

Standardised indicators like the SDGs are great for grantmakers who want to benchmark against other organisations within the sector. According to Our Community chief impact officer Jen Riley, standardised indicators enable you to compare your Granny Smiths with Royal Galas, rather than comparing them with oranges.

“If we’re all tracking towards the same goals and we’re all able to benchmark, then we’re contributing as a collective impact to those goals.”

There is a lot of overlap between the 17 SDGs, with some goals acting as umbrella goals covering many different subjects. Ms Riley encourages grantmakers to start off simply by picking one main goal they want to measure against.

“Wellbeing influences education, education has an impact on gender equality, for example. Pick a primary goal, and then a secondary, and go from there,” she says.

Measuring SDGs connects a global community of changemakers

Measuring using global indicators such as the SDGs can help Australian grantmakers consider their role in both a local and a global context, according to panellist Red Cross program officer Cara Tizon.

“Even though the goals are global, and they are obviously very ambitious and comprehensive, they are also applicable to the local context,” she said.

Placing your organisation’s own goals within the global context can also help you to connect with other groups working towards similar outcomes, said SmartyGrants managed services manager Alex McMillan.

“The idea and the design of that is to facilitate conversations between organisations that are working towards complementary goals,” she said.

“Organisations can get really in the weeds of what they're doing, but it’s important to lift that skywards, look outwards and connect with others. It’s a great example of what the SDGs can provide a community of people, and I think that that is very, very relevant for funders in Australia,” she said.

Ms Riley echoed that sentiment, saying, “The SDGs gives an overview of many, many issues, and then the importance of understanding where funding is going helps us understand whether we are funding what's needed.”

The study used the powerful social sector dictionary CLASSIE (developed by the Innovation Lab and SmartyGrants) to define subjects and beneficiaries, providing a detailed breakdown of who benefitted from the spending on each sustainable development goal.

Dr Oliva-Altamirano said the report was “designed to show grantmakers the overlap between SDGs, subject areas and beneficiaries” and to encourage them to “measure and target specific SDGs in their funding according to their theory of change”.

The analysis also highlighted some of the challenges of applying the SDG measures in an Australian context.

The SDG goals have an overarching aim of ending poverty, helping the world’s population lead prosperous and peaceful lives, and protecting the planet; but this doesn’t always translate to Australian funding priorities, partly because SDGs tend to focus on the needs of low-income nations, rather than wealthy countries such as Australia.

As a result, the analysis showed a significant gap between the globally recognised SDGs and the priorities of the Australian social sector.

Much of the spending on the visual arts, humanities, community celebrations and sport in Australia, for instance, isn’t captured by SDG goals, but instead relates to “higher order goals” that promote culture, self-esteem, creativity and knowledge.

The Innovation Lab study also summarised significant work by philanthropic groups and academics in Australia and overseas who are examining spending and policies that affect social development goals.

Dr Oliva-Altamirao said the value of the study would itself be measured by the impact it had on grantmaking processes in Australia.

The study is the latest report in the Innovation Lab’s Future of Funding series, which analyses funding by Australian grantmakers who use the SmartyGrants platform.